In music, you’ve probably heard of accidentals but might not know exactly what they are or why they’re needed.

Accidentals are a note or pitch that is not part of the key signature that you’re playing in. These notes are marked by using the sharp (♯), flat (♭), or natural (♮) signs.

But before that makes sense, we need to know what a key and key signature are. So, let’s start by looking at what a key is.

What Is A Key?

If a piece of music primarily uses notes from a certain type of scale, we say that piece is ‘in the key‘ of that scale.

For example, if we had a melody with the notes G – A – B – C – D – E – F#, then we are in the key of G Major because this melody uses only notes found in the scale of G major.

What Is A Key Signature?

To save us from always using a sharp or flat symbol every time, composers can use a key signature at the beginning of the staff to tell us what notes should always be played sharp (♯) or flat (♭) throughout the piece of music.

For a more in-depth guide to key signatures, check out our beginner’s guide to key signatures here.

What are Accidentals?

Sometimes, we might want to play a note that is not covered in the key signature at the beginning of the piece.

For example, in the key of G Major, the notes we would play are G – A – B – C – D – E – F♯, but what if we want to play a B♭ or a C♯?

This is where accidentals come in. Accidentals are a note or pitch that is not part of the key signature that you’re playing in. These notes are marked by using the sharp (♯), flat (♭), or natural (♮) signs.

Accidentals change the note they accompany either by raising or lowering it by a half step (semitone).

The ♯ sign raises the note a half step, the ♭ sign lowers the note a half step, and the natural sign ♮ either raises or lowers the note, depending on the key signature.

How To Use Accidentals

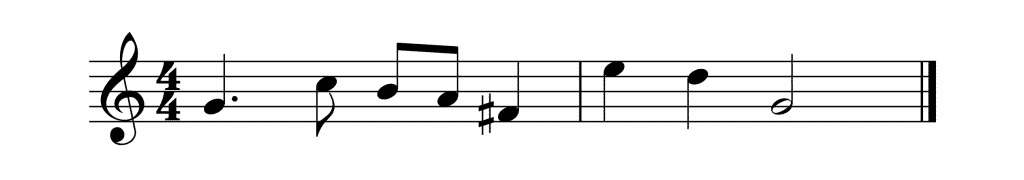

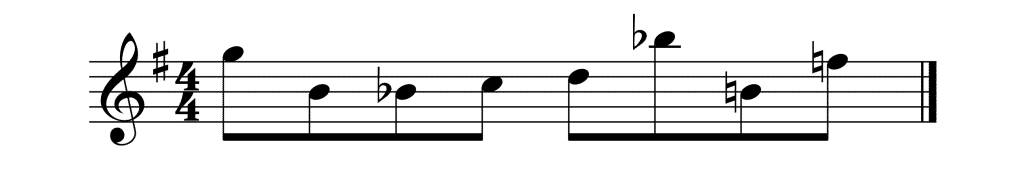

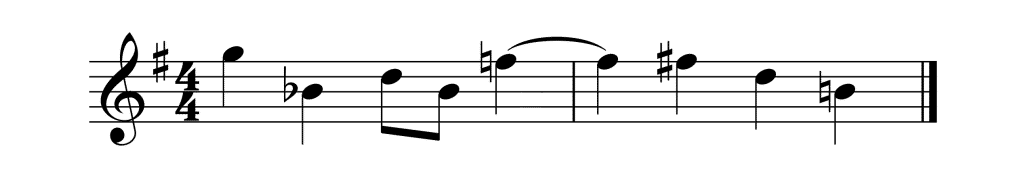

Here is an example of a melody that uses accidentals.

The key signature tells us that we’re in G Major, so that means that all notes are natural notes, except for the F – in this key, you have to play an F♯ whenever you see a note on the F line or space.

See the♭and♮signs in the second measure? Those are the two accidentals in the melody. They change the notes you would normally play in this key signature from B♮and F♯ to B♭and F♮, respectively.

However, there are two specific rules that apply to accidentals that affect not just the note the accidental is on but other notes as well.

The first rule is that the accidental is applied first to the note it is next to (see the first B♭in the second measure), and it is also applied to every repetition of that note for the rest of the measure.

Because of this rule, the second B in the second measure is also a B♭. We don’t have to add another Bb to the second B in measure two because this could cause the music to look overcrowded and hard to read.

If a note with an accidental is repeated an octave higher or lower (within the same measure), the accidental doesn’t usually apply to this note (although there are some that say it does).

To clear up any misunderstanding, it’s common to mark with another accidental any instance of that note with another flat or sharp sign (if the accidental carries over) or with a natural sign to indicate that it doesn’t apply.

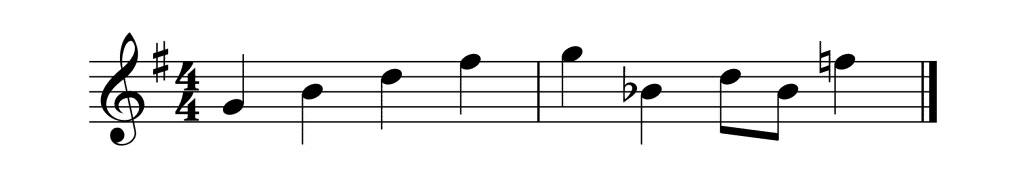

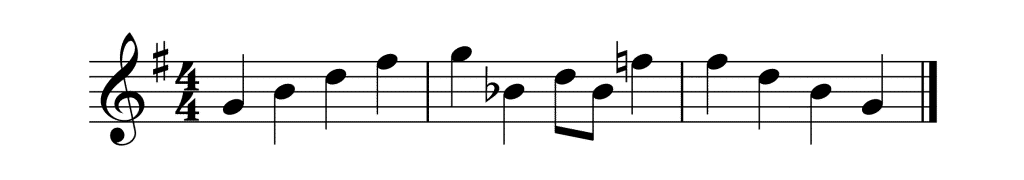

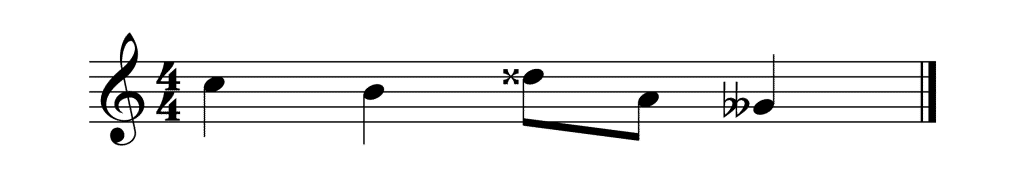

For example, here is a measure in which the B starts as a B♮because of the key signature, then changes to a B♭with the first accidental.

If we wanted the next B, an octave above, to also be played as a B♭we add another ♭symbol. However, the following B is back to B♮because it has a natural, accidental sign next to it.

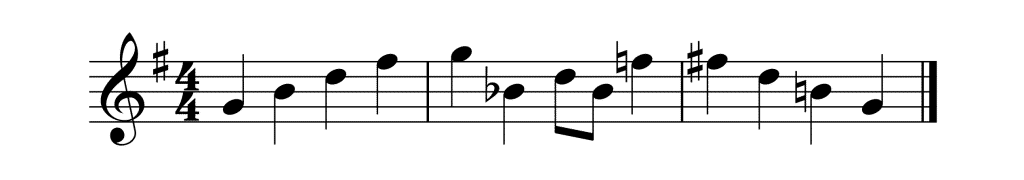

The second rule is that the accidental does not carry over into the next measure.

In this example, the B and the F in the second measure are a B♭and an F♮. However, once we go over the bar line into the third measure, these accidentals are wiped clean, and the notes are back to the regular key signature.

This means that in the third measure, the F is an F♯ , and the B is a B♮.

But, it’s the convention to remind the musician that they are back to the key signature by adding another accidental to match the key signature. So in this example, adding an F♯ and a B♮.

Accidentals with tied notes

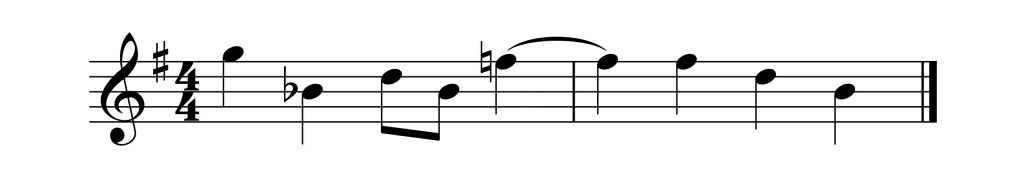

The only exception to this rule is when the note is tied over the bar line, meaning the two consecutive notes are played as one.

When the notes are tied, the accidental is kept for that note only, and the next note played is back to the normal key signature unless the accidental is repeated.

For example:

In this example, the F♮is tied over the bar line, meaning the F on the first beat of the second measure is also an F♮. However, the F on the second beat, because it is not tied, is back to an F♯.

At the same time, the B♭in the second measure is held throughout that measure only, and the next time the B is played (in the third measure), it is back to being a B♮.

But, as before, it’s the convention to mark both of these notes with another accidental to tell the musician that they revert back to the key signature.

Double Accidentals

There are also accidentals that are called double accidentals. These are much rarer than regular accidentals, and they raise or lower a note by two half steps.

There are no double natural accidentals, but only double sharps (♯♯, more commonly seen as ‘x’) and double flats (bb).

Here is an example of both:

The D has a double sharp accidental next to it, raising it two half steps, and the G has a double flat accidental, lowering it two half steps.

The reason you see double accidentals so rarely is that a D raised by two half steps is enharmonically equivalent to (in other words, it sounds the same as) an E♮, which is in the key signature of C Major.

The same is true for the G♭♭, a G lowered by two half steps is the same as an F♮.

In both cases, it would make more sense to simply write the notes as an E♮or F♮, respectively.

So, the only time you would normally see double accidentals is in keys that already have many sharps or flats, keys like C♯ or F♯ for sharps, or D♭or G♭for flats.

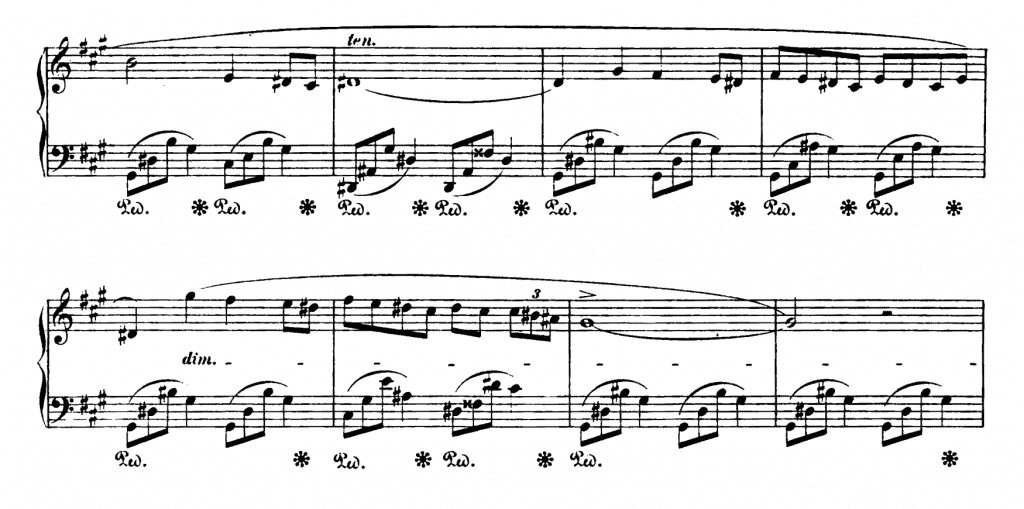

Here is an excerpt from a Chopin piece titled “Nocturne in F♯ Minor, Op. 48 No. 2”.

As you can see in the second and sixth measure, in the bass clef, there is an F double sharp (Fx).

That’s Accidentals

So that’s all there is to know about accidentals. Just know that when you see one in a piece of music, that means to play the note differently than it is usually played in the key signature that you’re in.

Let us know if you have any questions or if we missed anything, and we’ll add it in!