The term enharmonic if you haven’t heard it before, can be quite confusing. You’ll often get asked about it in a grade five music theory exam so it’s definitely worth learning for some easy marks.

In this post, we’re going to be looking at some examples of what enharmonic equivalents are and how they’re used in reading and writing music.

What Does Enharmonic Equivalent Mean?

Although it sounds quite complicated, an enharmonic equivalent is an ‘alternate name for the same thing.’

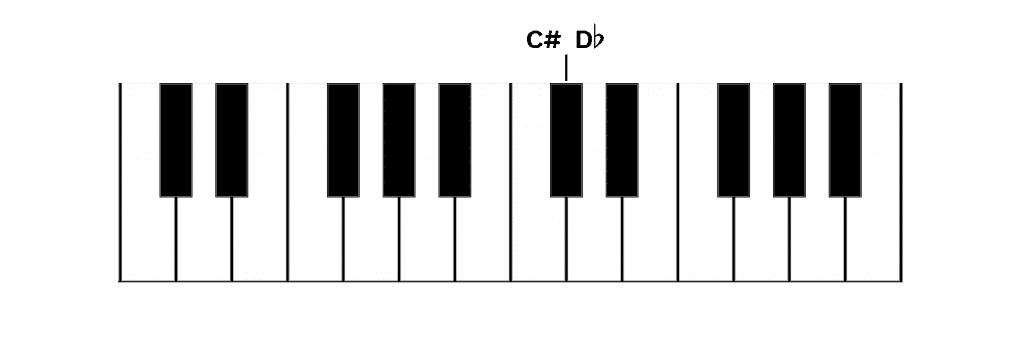

For example, you could have a note like C#, but you could also call this note Db.

Or the chord Eb Major, is the same notes as Db major.

In these two cases they have the same notes but have different names, and so are enharmonic equivalents.

Types of Enharmonic Equivalents

There are actually lots of different types of enharmonic equivalents.

You can have an enharmonic equivalent:

- Note

- Scale

- Chord

- Key

- Interval

We’ll go into some examples now to explain how they work.

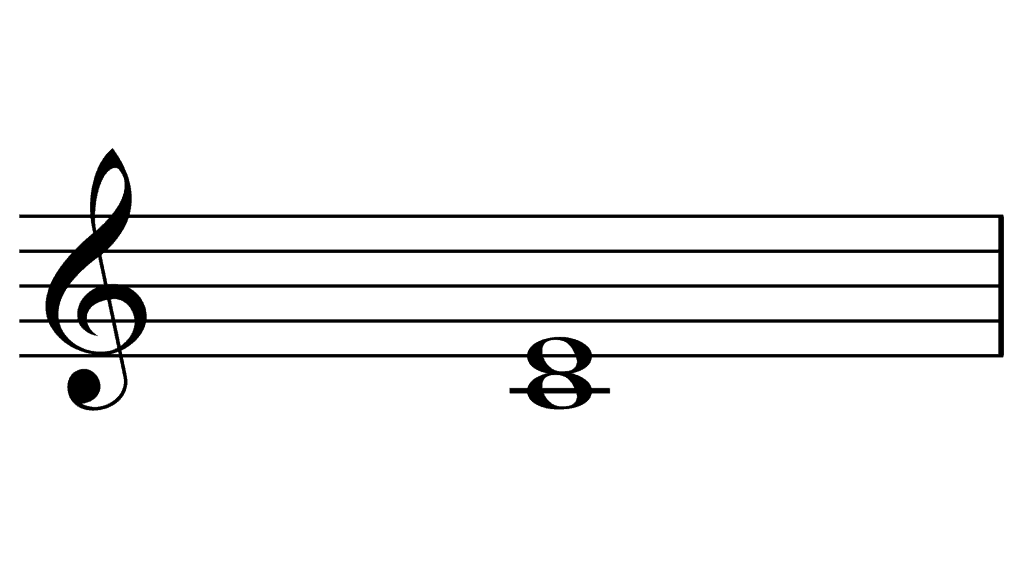

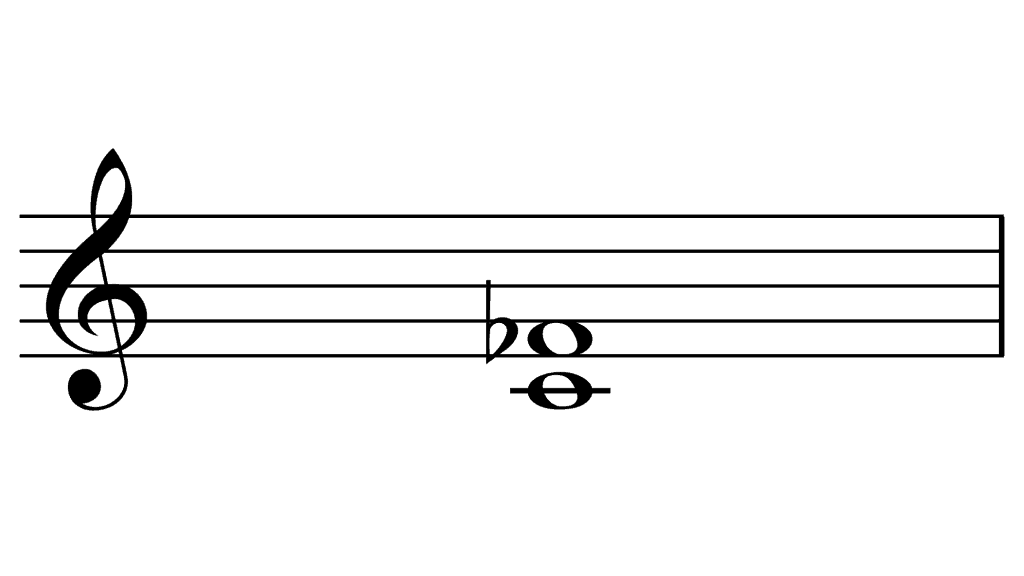

Enharmonic Equivalent Notes

Notes can have more than one name.

For example, this note here could be either C sharp (C#) or D flat (Db) depending on how you look at it.

You could also call it B double sharp, all are correct but it depends on what context you’re playing the note.

When you have notes like this that are the same but with different names, they are called enharmonic equivalents.

Whether you’d call it D flat, C sharp or B double sharp depends on what key you’re in.

For example, if we were in the key of Ab then we’d call this note Db as Ab has four flats in its key signature: Bb, Eb, Ab and Db.

But if we were in the key of E major, then it would be C# as E major has four sharps in its key signature: F#, C#, G#, and D#.

If we were in the key of C# major then it would be B double sharp as C# major has seven sharps it its key signature: F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, and B#

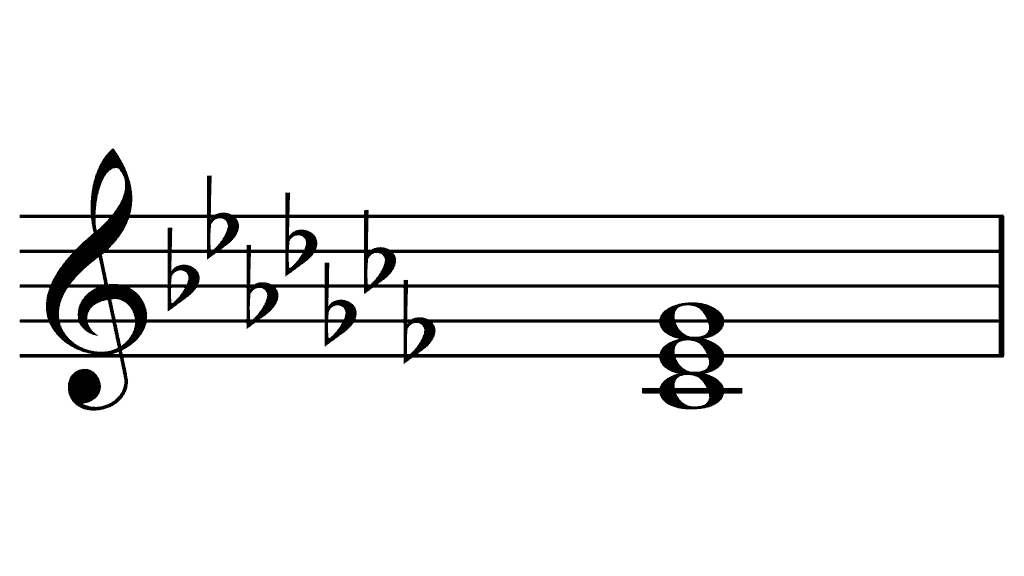

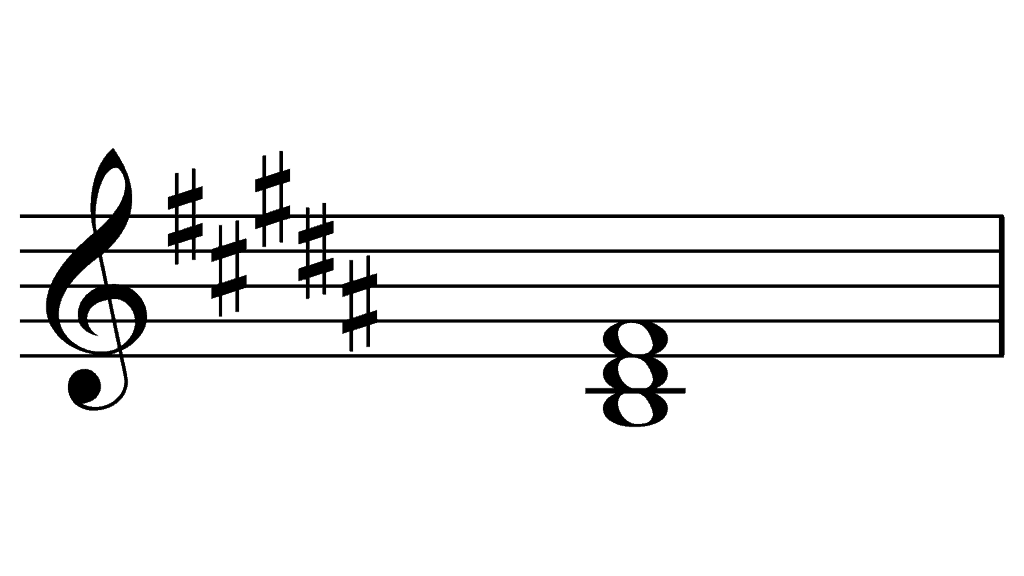

Enharmonic Equivalent Scales

As well as enharmonic equivalent notes you can have enharmonic equivalent scales and they work in exactly the same way.

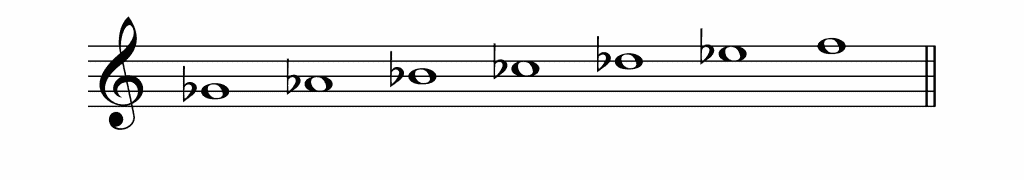

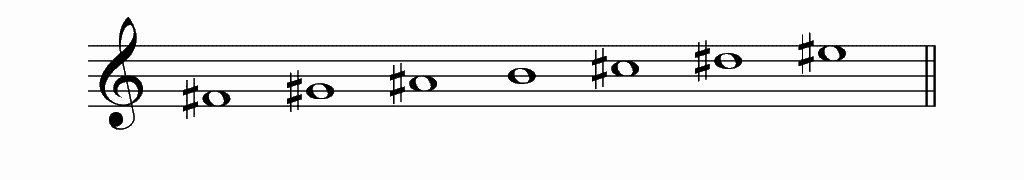

For example, if we take the scale Gb major, which has the notes: Gb – Ab – Bb – Cb – Db – Eb – F

The enharmonic equivalent scale would be F# major, which has the same notes but spelled differently: F# – G# – A# – B – C# – D# – E#

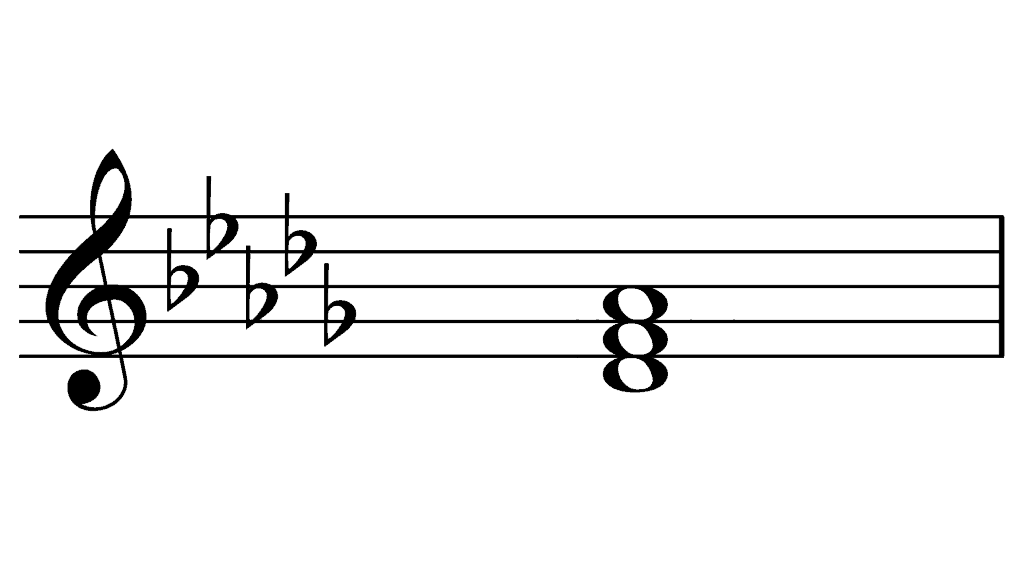

Enharmonic Equivalent Key and Chords

An enharmonic equivalent key is one that has the same pitches but with different names.

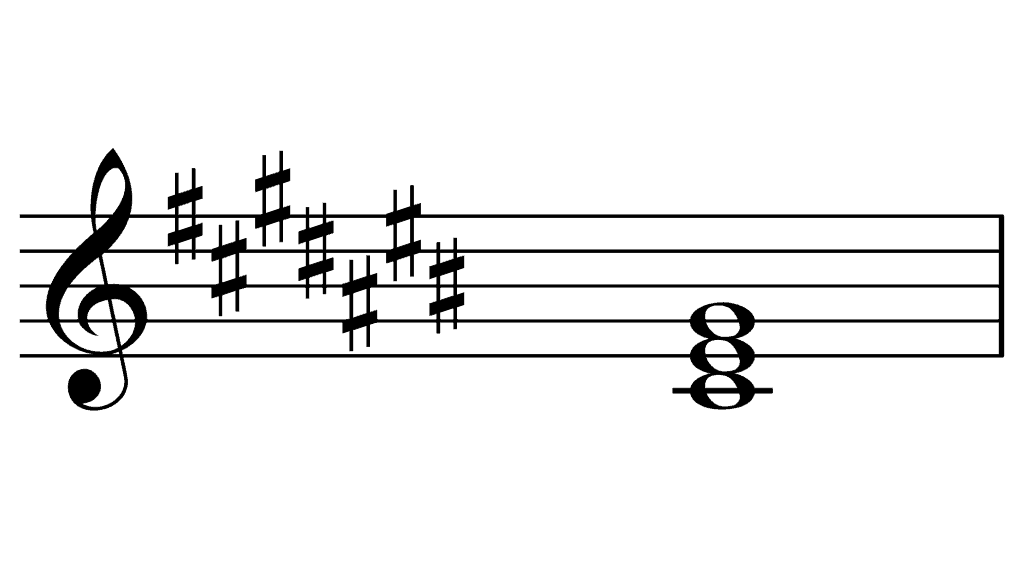

It works in the same way as scales and notes. For example, C# major and Db major are enharmonic equivalent keys as the underlying pitches are the same, but C# major uses sharps, and Db major uses flats.

You might wonder why you might use one key over the other.

The main reason is that some keys have fewer flats or sharps than others and can be a lot easier to read.

For instance, in the case of C# and Db major, most people would prefer to play in Db major as it only has five flats as opposed to C# major, which has seven sharps.

Or if you had the choice of playing in Cb major (which has seven flats) or B major (which has five sharps) which would you choose?

Enharmonic Equivalent Intervals

Enharmonic equivalent intervals are slightly different from notes, scales and keys but follow the same principle.

An enharmonic interval is two notes that are the same distance apart but spelt differently.

For example let’s take the two notes C and E which is a major 3rd.

But, Fb is an enharmonic equivalent of E natural so we could also write this interval as C to Fb which although is the same amount of semitones apart is now described as a diminished 4th instead of a major 3rd.

Wrapping up Enharmonic Equivalents

I hope that helps make a bit more sense of enharmonic equivalents.

It can seem a bit confusing and overwhelming at first, but once you get the hang of seeing notes, scales, keys and intervals as being more than one thing it should start to sink in.