Harmony is a word that is essentially synonymous with music itself. When it comes to music theory, harmony is the most analyzed topic by far – every analysis you read about a piece of music will be focused mainly on harmony. It, along with melody and rhythm, make up the ‘big three’ with regard to music terminology.

Nevertheless, harmony as a term is still misunderstood by a lot of musicians. This post seeks to answer the question of what harmony is in music and how it is used.

The Definition of Harmony

In simple terms, harmony is what occurs when more than one note is played or sung at the same time.

This can be as an interval (two notes, also called a dyad), or chords of three or more notes.

Check out our posts on intervals and chords if you want to learn more about them.

One way to think about harmony is that it deals with the ‘vertical’ aspects of music, whereas melody and rhythm deal with ‘horizontal’ aspects.

As you can see in the example below, only on the final two beats of the measure does harmony appear, and it’s easy to see because there are notes stacked ‘vertically’ on top of each other.

This video from Jacob Collier explains harmony to five different people in increasing levels of complexity and is definitely worth a watch.

Consonance and Dissonance

Just because two simultaneous pitches produce a harmony does not mean they sound ‘harmonious’ together.

Harmony is simply whatever sound they do produce, and a ‘harmonious’ sound means something pleasant or nice sounding.

Harmony can be nice sounding – and the term for this is called consonance.

However, it can also sound rough or irritating, which is what we call dissonance.

Consonance

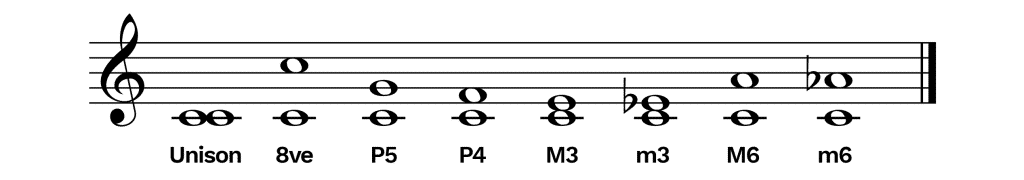

Consonant intervals and chords produce a feeling of calmness and of rest.

Intervals that are considered consonant are unison (both people playing the same note) and octaves,

Perfect 5ths and 4ths (G – D or G – C), major and minor 3rds (F – A or F – Ab), and major and minor 6ths (D – B or D – Bb).

Also, the compound versions of these intervals are consonant as well.

Here are all the consonant intervals from middle C:

The major and minor triad chords are also consonant because they’re made of all consonant intervals.

For example, in a C Major triad (C – E – G), the C – E interval is a consonant major 3rd, the E – G interval is a consonant minor 3rd, and the C – G interval is a consonant Perfect 5th.

Most songs begin and end on consonant intervals and chords, because consonance is generally considered ‘relaxed’, and when you play consonant harmonies they don’t feel like they have to ‘go’ anywhere.

Whether a piece is in a major or minor key, it will most likely start and end with consonance (except in jazz and film music, both of which are genres that are based around dissonant chords rather than consonant).

Dissonance

Dissonant intervals and chords produce a feeling of tension and movement.

Intervals that are considered dissonant are major and minor 2nds (C – D or C – Db), major and minor 7ths (B – A# or B – A), and augmented and diminished 4ths and 5ths (F – B or F – C#), and the compound versions of them.

Here is a list of the dissonant intervals from Middle C:

One weird thing about this is that the Aug5 (C – G#) and Dim4 (C – Fb) intervals are enharmonically equivalent to the consonant intervals min6 (C – Ab) and Maj3 (C – E), respectively.

However, when they are written as diminished or augmented intervals they are dissonant, and only when they are written with the correct letters for the major/minor intervals are they consonant.

For example, in C# Major, the interval C# – F is dissonant (Dim4) but the interval C# – E# is consonant (Maj3).

Dissonant chords and intervals are usually found in between consonant ones, and rarely for very long.

They are inherently less ‘stable’ than consonant chords, and so usually when you play a dissonant chord it ‘resolves’ to a consonant chord.

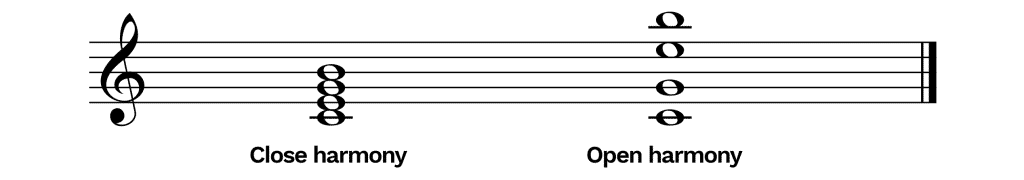

Close vs Open Harmony

When playing a chord, you can play it in either what is called close or open harmony.

Close harmony is, like it implies, when the notes of a chord are close together.

So, if you start with the root of a chord (the note the chord is based on), then the next closest note you can play is the 3rd above the root.

From the 3rd, the next closest note you can play is the 5th, and from the 5th the next note is the 7th, and so on.

Open harmony is when the notes in a chord are more spaced out, and uses compound versions of intervals, like 10ths and 12ths instead of 3rds and 5ths.

Here is a C Maj 7 chord (C – E – G – B) written in close and open harmony:

Even though they are both made of the same notes, the two chords above sound different because one is tight and close together, and the other is very open and spanning multiple octaves.

How Harmony Works

Most music you listen to is called tonal music, which means it’s music that is centered around a single tone, called the tonic note (see our post on scale degrees for more info if you need).

In the key of C Major or Minor, the tonic note is the C, and the chord that is built on C (C Major or C Minor, respectively) is called the tonic chord.

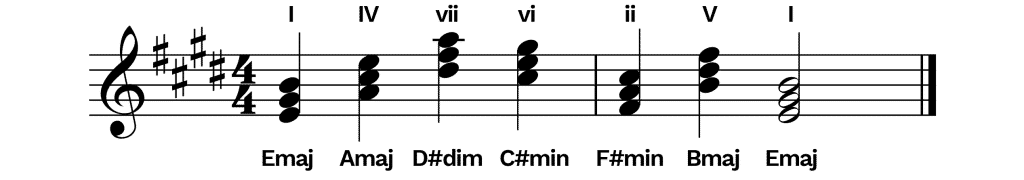

In tonal music, there are three categories that chords fall into, based on their function in a song: tonic, dominant, and predominant.

Tonic

A tonic chord is a chord that is stable, and one that feels like you don’t have to move anywhere from it.

Besides the main tonic chord that we mentioned above, other chords that could function as tonics are the iii chord (so an E Minor chord in the key of C Major) and a vi chord (A Minor).

Dominant

A dominant chord is the opposite of a tonic chord.

It is a chord you want to move away from, and usually comes right before a tonic.

The two chords that are dominant chords are a V (G Major in the key of C Major) and a vii (B dim in the key of C Major)

Predominant

A predominant chord usually bridges the gaps between tonic and dominant, and adds color to a chord progression.

There are two predominant chords – the ii (D Minor in the key of C Major) and the IV (F Maj).

Here’s an example chord progression that shows the proper function of the tonic, predominant, and dominant chords, in the key of E Major:

- I – tonic

- ii – predominant

- IV – predominant

- V – dominant

- vi – tonic

- vii – dominant

This was a very quick overview of how harmony functions in tonal music.

Check out our other post on cadences for a more in-depth look at harmonic motion.

Summing Up

Those are the basic elements of harmony!

It is a very, very deep and detailed topic to get into, but we hope this was a helpful introduction.

Harmony informs almost all of music theory, and essentially is the basis of musical analysis for every type of music, from classical to jazz to pop music.