There are lots of different types of scales in music. Some have seven notes, some have five, some sound happy, and some sound sad. However, there is one type of scale that uses all twelve pitches in western music called the chromatic scale.

In this post, we’re going to take a look at what a chromatic scale is, as well as some of the rules around how to properly notate it.

What is a Chromatic Scale?

Put simply, a chromatic scale is all twelve notes arranged in ascending or descending order of pitch.

It’s made up entirely of half steps (semitones), with each note being a half step above or below the last note.

On a piano, that means playing all the white notes and all the black notes in order of pitch like this:

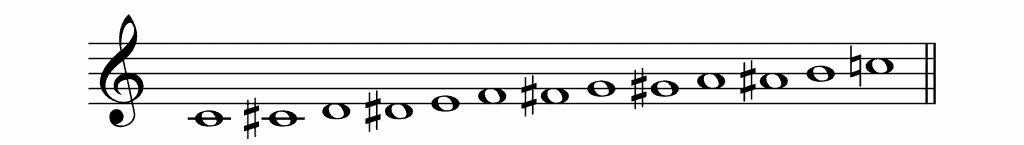

Here is an ascending chromatic scale, starting on C written out on a stave:

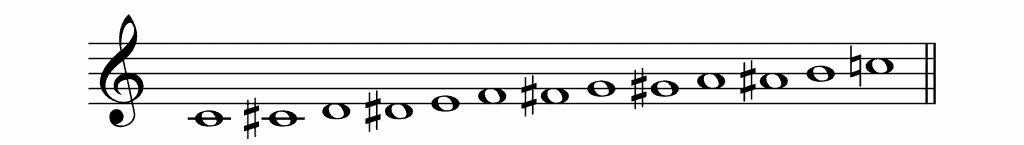

Here is a descending chromatic scale starting with C:

But you can start a chromatic scale on any note; just play the note one half step higher until you reach the starting note an octave above.

To descend, you play the note one half step lower until you reach your starting note.

What Does Chromatic Mean?

The word chromatic comes from the Greek word “chroma” which means color.

We use the word chromatic as it allows us to add color and embellish the notes of major and minor scales.

During the 1600s, music was generally written in major and minor keys. Composers used notes outside of these keys (called accidentals) to embellish the melody and add color to the music.

This is why we call them chromatics, as they bring color and emotion to the music without changing the key center.

From the 19th century onwards, composers wanted to get away from writing music in a given key. This led to chromatics being used more and more and gave rise to atonal music, which doesn’t have any sense of tonality.

How to Notate a Chromatic Scale?

Unlike most music scales, which have only one correct way to notate them, you can write a chromatic scale in a number of different ways.

For example, you could start a chromatic scale with the notes C, C sharp, and D:

But you could also notate it with the notes C, Db followed by D natural:

Both of these are okay, but there are a few rules and conventions to follow.

Ascending and Descending Chromatic Scales

The first thing to mention is that it’s common to use sharp signs when writing an ascending chromatic scale:

Then use flat signs when writing a descending chromatic scale:

In practice, composers will write in the most convenient way, taking into account any notes in the key signature as well.

But, in the context of music theory, there are two rules that you must follow when writing a chromatic scale which are:

- You must have at least one note on every pitch

- You must not have more than two notes on any pitch

I’ll explain what I mean by these two rules with some examples.

One Note on Every Pitch

It’s really important when notating a chromatic scale to have at least one note on every single pitch.

You don’t want to be skipping notes.

For example, you could write a chromatic scale like this, which, if you were to play it, would be a chromatic scale.

But if you look closely, you’ll see that there is no note on the pitch E so this would be incorrect, especially in a music theory exam.

Make sure that you have at least one note on every line and space of the stave.

No More Than Two Notes on any Pitch

The other rule to follow when notating chromatic scales is that you must not have more than two notes on any one pitch.

This is best shown in another example.

Below we have another chromatic scale starting on C which if you were to play, would sound a chromatic scale.

But this would be another incorrect way of writing a chromatic scale as it has more than two types of the pitch C.

It starts on C, then C sharp followed by C double sharp.

Make sure you don’t have more than two notes on any one pitch.

Chromatic Solfege

Solfege is the system that we use to name each of the syllables in a major scale.

If you’ve seen the film The Sound of Music you’ll know them:

Do – Re – Mi – Fa – Sol – La – Ti – Do

But what about the syllable names of the chromatic notes?

For this, we have to add some other syllables known as chromatic solfege, which when ascending, are:

do di re ri mi fa fi sol si la li ti do.

When descending, we then use the following syllables:

do ti te la le sol se fa mi me re ra do

Watch the video below to hear how this sounds.

Examples of the Chromatic Scale in Classical Music

There are lots of examples from classical music where composers have used chromatic scales to add color and emotion.

Below, I’ve listed a few of my favorite examples of music that uses chromaticism.

Etude Op 25 No.6 – Chopin

A great example of using the chromatic scale in classical music is this fantastic piece by Chopin.

It uses chromatic thirds to create a really interesting sound.

Check it out below.

Fantasia in D Minor – Mozart

Another good example of chromatic scales is Mozart’s Fantasia in D minor.

At 3:20 you’ll hear a cadenza followed by an ascending chromatic scale into the next section.

Flight of the Bumblebee – Rimsky-Korsakov

Another very famous piece is The Flight of the Bumblebee by Rimsky Korsakov.

Here, it is arranged for piano, and as you’ll see, it uses a lot of chromaticism.

Summing up Chromatic Scales

I hope that helps make a bit more sense of chromatic scales in music theory.

They’re a really important scale to learn and come up a lot in music, so it’s definitely worth learning about them.

If you have any questions that I haven’t covered, let me know and I’ll do my best to answer and update this post.