In music, most pieces and songs are made primarily of chords. They are the basic unit of harmony, one of the fundamental aspects of music. There are many types of chords, like Major and minor, or Seventh chords, and it’s important to learn all of the different kinds.

In this article, we’ll discuss Altered Chords. What are they, and how do we make them? To learn all about Altered Chords, first we need to know exactly what a chord is.

What is a Chord?

A Chord is basically any time more than one note is played simultaneously.

Chords can have only two notes – these are called intervals or dyads – but the vast majority have three or more notes.

Here is a post we wrote about all the different types of chords if you want to go deeper but we’ll give a quick overview here.

Most of the time chords – especially chords with three or more notes – are created by stacking intervals of a 3rd on top of each other.

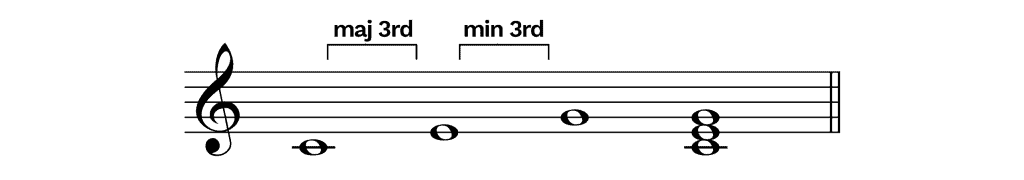

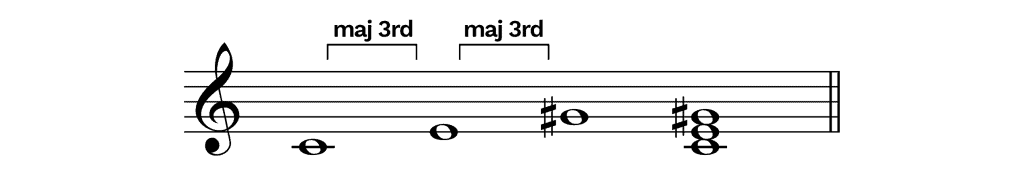

A minor 3rd interval is 3 semitones (or half steps) and a Major 3rd interval is 4 semitones.

A major triad (a triad is a chord with three notes) starts with a major 3rd and then stacks a minor 3rd on top.

So, starting on C – a Maj 3rd goes up 4 semitones to E, and then a min 3rd from E goes up 3 semitones to G – therefore a C Maj triad is written C – E – G.

You can also figure out a chord by taking every other note from the diatonic scale that the chord is a part of.

Definition of Altered Chords

We can give the notes of a chord numbers to keep track of them better.

This also allows us to switch between chords in different keys, because a major chord will always have the same intervals between the notes.

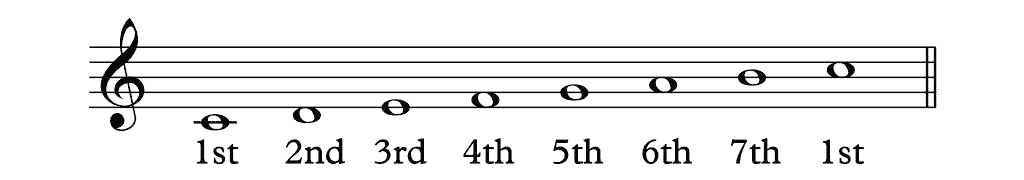

Let’s give the C major scale numbers instead of letter notes:

Instead of using 1st, 2nd, 3rd etc. a lot of the time you’ll see these represented as Roman numerals.

Therefore a Maj chord uses the numbers I – III – V, and if it’s a seventh chord you add the number VII.

There are also extended chords that use numbers greater than VII – these are called 9th, 11th, and 13th chords.

An altered chord is when you change one or more of the notes in a diatonic chord (a chord taken from a diatonic scale, as shown above) by either raising it or lowering it a semitone.

If we’re in C major like the scales above, a dominant chord (which would be G major) would use the notes G – B – D.

However, if we lower the 3rd from B to Bb, or raise the 5th from D to D#, then we have an altered chord because it uses a note that doesn’t show up in the normal scale.

One common type of altered chord is the augmented chord which is when the 5th note of a major chord is raised one semitone.

An example of this would be C major augmented chord (a type of altered chord) which would use the notes C – E – G#.

Here the G natural is altered and raised one semitone to G#.

Alt Chords

The most common notes that are changed in an altered chord are the 5th and the 9th degrees.

This is especially the case with a dominant chord, which is a major chord that has a flattened 7th.

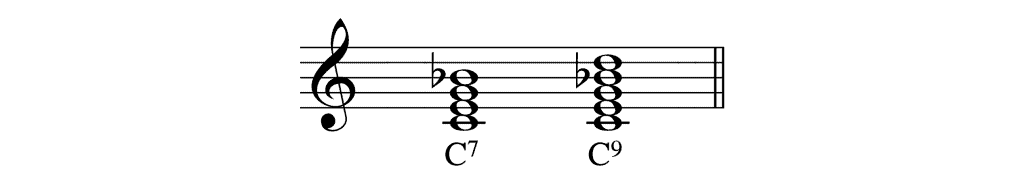

With a C7 (dominant) chord, you have C – E – G – Bb, and if you add the 9th it’s C-E-G-Bb-D.

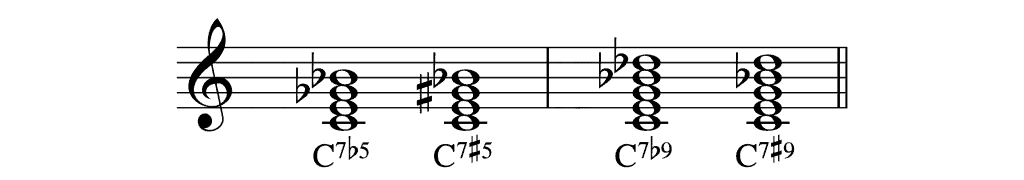

An altered chord would either raise (#) or flatten (b) the 5th or 9th (Gb or G#, Db or D#), so you could have C7b5, C7#5, C7b9, or C7#9.

These types of chords are called “Alt” chords, and you most likely will see them in Jazz music.

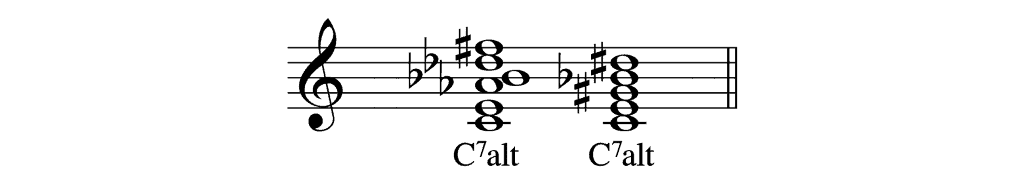

Instead of adding all of the different configurations of the flattened or raised 5th and 9th, you just need to write this chord as C7alt.

An “alt” chord has the following notes:

- root (I)

- 3rd

- b5 and/or #5 (b5 is often written as #11)

- b7

- b9 and/or #9, and b13

Here are two ways you can write out an Alt chord.

They’re usually not specified as to which way you have to write them, so it’s up to you as a player or composer whether you want to have a b5 or #5 or both, or b9 or #9 or both also.

Borrowed Chords and Secondary Dominants

Using the broadest definition any chord with a non-diatonic note in it can be considered an altered chord.

The two most common types of chords that feature non-diatonic notes are:

- Borrowed chords

- Secondary dominants

Borrowed Chords

Borrowed Chords are chords in a specific key that “borrow” notes from the parallel major or minor key.

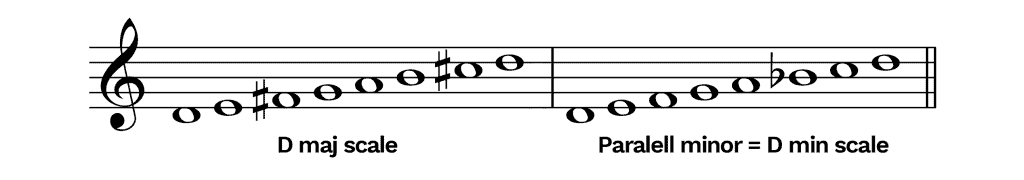

For instance, if we’re in D major, the parallel minor is D natural minor:

D – E – F – G – A – Bb – C – D.

So, if a chord that is diatonic to D Major (G Major, E minor, A Major, etc.) were to borrow a note from the D minor scale, it would become a borrowed chord.

A G minor chord is G – Bb – D, which uses the Bb from the D minor scale, and would be considered a borrowed chord if the song we’re playing is in D Major.

Same with an A minor chord, or a C Major chord, or even D minor.

Secondary Dominants

A Secondary Dominant, on the other hand, is a dominant chord (a seventh chord with a Maj 3rd and a min 7th) that resolves to any note besides the tonic.

What this does is it typically alters either the 3rd (raising it to make it Maj) or the 7th (flattening it to make it minor).

In the D Maj scale above, the F# chord would be minor (F# – A – C# – E), so to make it an F#7 chord, we’d need to raise the 3rd to become F# – A# – C# – E.

This alters the A, making it non-diatonic.

An example of secondary dominants can be found in Don’t Know Why by Jesse Harris. In Norah Jones’ cover, which is in Bb major, you’ll hear a C7 chord (In the key of Bb major you’ll have an Eb but it’s been raised by a semitone to E natural).

Altered Chords Summed Up

We hope this article was really helpful to help you learn all about Altered Chords.

Just as its name implies, an altered chord is at the most basic level a chord with one or more notes altered – raised or flattened a semitone – to make them non-diatonic.

From there, the rest is just a matter of which notes to alter and how you want the chord to sound.