Chords are the basic building block for music harmony, and therefore, you’ve almost definitely heard a lot about them. But there are a lot of different kinds of chords, and not many people know exactly what they are and how to make them.

Let’s take a look at all the different types of chords, but first, what is a chord?

What Is A Chord?

The definition of a chord is a group of two or more notes played at the same time.

These notes will usually complement each other, which then creates harmony.

On top of the harmony, you’ll then have a melody played.

Different Types Of Chords

We can categorize chords in a number of different ways.

One way to sort them is by how many different notes each chord has, which results in them having a different name.

Let’s take a look at what chords are called if they have two, three, four, or more notes.

Two Note Chords: Dyads

A chord that consists of only two notes is called an interval or a dyad.

Any two combinations of notes can technically be considered a dyad, but the most common ones you see have an interval of a 3rd between them.

For example, a dyad of C – E would be one that suggests a key of C major because it contains two of the three notes of a C major triad chord.

So, let’s take a look at triad chords next.

Three Note Chords: Triads

Triads are the most common type of chord in music. They are made up of three notes, which is why they’re called triads.

The “tri” in triad comes from the Greek word meaning “three,” which is where we get words like triathlete and triangle.

Triads are built using three particular notes: the root, 3rd, and 5th, with each note being an interval of a 3rd apart.

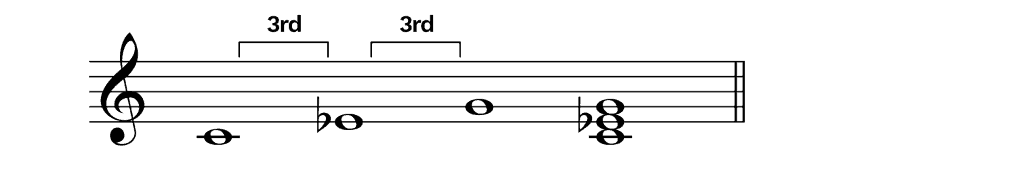

For example, here is a C major triad with each interval between the notes being a 3rd.

To learn more about all the different types, check out our guide to triad chords here.

Four Note Chords: Tetrads

Chords with four notes are called tetrads.

The word “tetra” means “four” in Greek and is from the same root as a tetrahedron (a shape with four faces).

There are a few different types of tetrads, with the most common type being seventh chords, but we’ll cover these and some others later in this post.

Chord Qualities

Just like with scales, the type of chord you play depends on the intervals between each note. We call this the quality of the chord.

The quality of the chord affects how it sounds. For example, you could say a major chord sounds happy or a minor chord sounds sad.

Let’s take a look at the five types of chord quality.

Major Chords

A major chord is one that has a note that is a major 3rd (4 half steps) away from the root of the chord.

So, in a C major chord, you would expect to see an E in the chord. In an A major chord, you would see a C#.

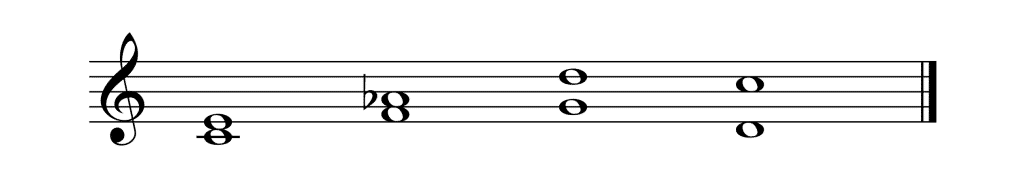

The octave and order of the notes don’t matter very much. For example, the following chords are all E major triads:

If you have a major 7th chord or extended chord, the 3rd and the 7th have to be major.

Minor Chords

Just like with major triads, what makes a minor triad minor is that there is a note in the chord that is a minor 3rd (3 half steps) away from the chord’s root.

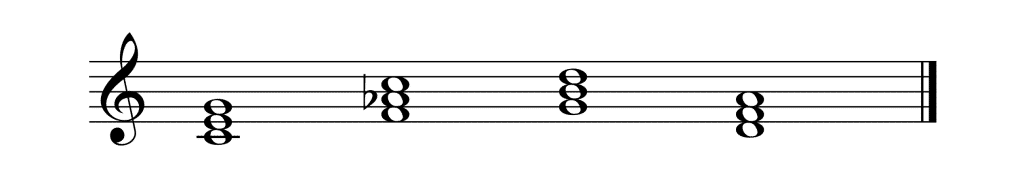

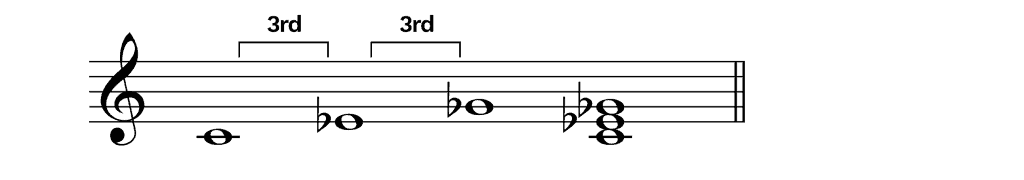

For example, here is a C minor chord, and you can see that the interval between the 1st and 2nd notes is a minor 3rd.

In a tetrad or extended chord, both the 3rd and 7th need to be minor intervals, but we’ll talk about those a bit later on when we look at extended chords.

Diminished Chords

A diminished chord is made up of minor 3rd intervals. So not only are the 1st and 2nd notes a minor 3rd apart but the 2nd and 3rd are also a minor 3rd.

This means that it also has a diminished 5th interval (6 half steps) in it.

A C minor chord would have C – Eb – G, but the diminished chord flattens the G to a Gb.

For a diminished 7th chord, you have two options:

- A half diminished chord

- A fully diminished chord

A half-diminished chord keeps the minor 7th, so it therefore would have the notes C – Eb – Gb – Bb.

A fully diminished flattens the minor 7th down a step to become enharmonically equivalent to a major 6th (9 half steps).

A C fully diminished 7th chord would comprise C – Eb – Gb – Bbb (B double flat, equivalent to an A).

Augmented Chords

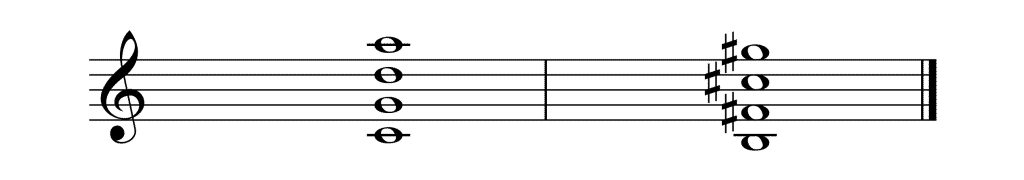

The opposite of a diminished chord, an augmented chord, is when you take a major chord and raise the 5th one half step so that it is eight half steps away from the root.

This way, it’s made up of two major 3rd intervals (whereas a diminished has two minor 3rd intervals).

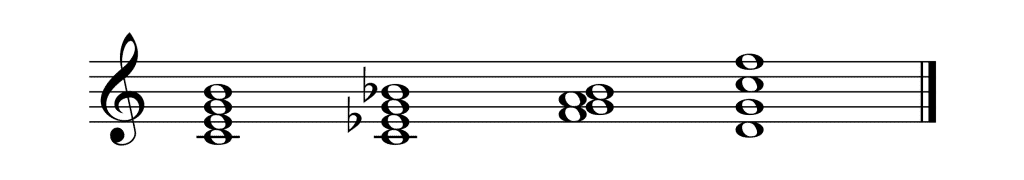

For example, here is a C augmented triad:

Other Types Of Chords

There are a few other types of chords that you might need to know about. These types of chords are very common in jazz music.

Seventh Chords

A seventh chord gets its name because it uses the 7th scale degree.

As we said above, a triad chord uses the root note, the 3rd scale degree, and the 5th scale degree to make a chord.

So if an E major scale is E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D# – E, then the E major triad would be the 1st, 3rd, and 5th letter: E – G# – B.

A seventh chord adds an extra note to the triad, and the note that it adds is the 7th scale degree.

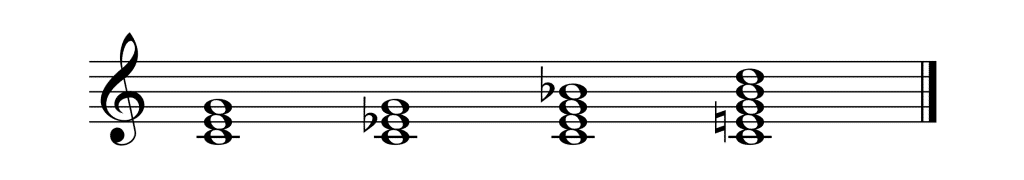

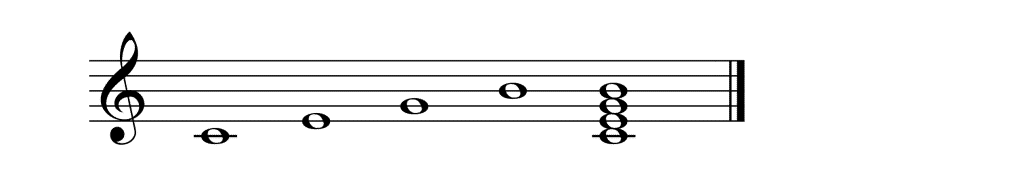

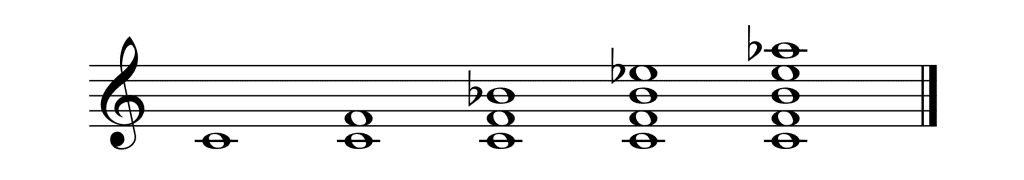

So a C major 7th chord is C – E – G -B:

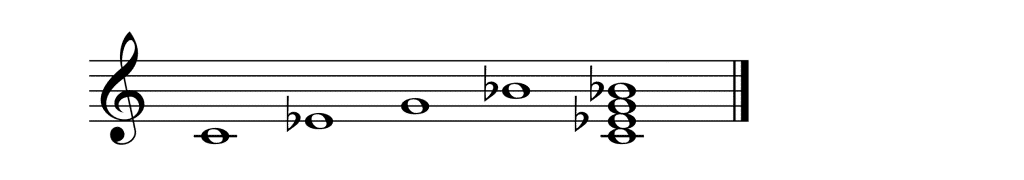

And a C minor 7th chord would be C – Eb – G – Bb:

For more info, read our in-depth post on the different types of seventh chords here.

Dominant Chords

A dominant chord is like a mixture of major and minor; it is what happens when you have a major 3rd interval (like in a major chord) and a minor 7th interval.

It gets its name from being the chord from the fifth note of the scale, which is called the dominant.

If you know about the Mixolydian mode, the dominant chord is made from the same scale.

In C, a major 3rd is E♮ , and a minor 7th is Bb, so a C dominant 7th chord would be C – E – G – Bb.

Extended Chords

An extended chord, as the name implies, extends past the 7th scale degree.

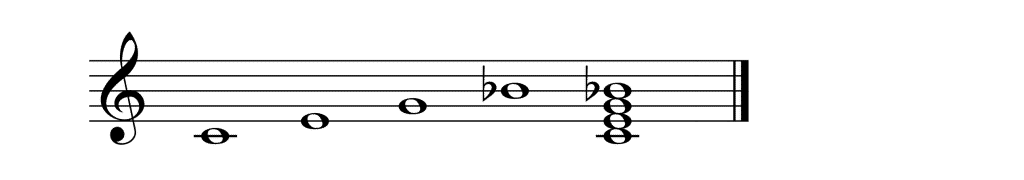

Take a look at this C major scale that spans two octaves:

Underneath the notes are the scale degrees: 2nd, 5th, 11th, etc

As we covered earlier, a C major chord (1 – 3 – 5) would be C – E – G, and adding a seventh would give you a Cmaj7 chord of C – E – G – B.

However, we can also add the 9th, the 11th, and the 13th to our chords.

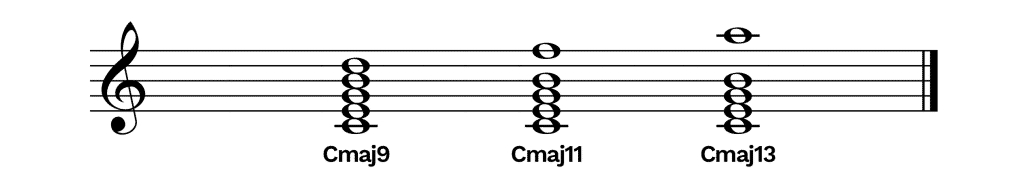

Chords with these scale degrees are called extended chords, and you would write them in C major as a Cmaj9, Cmaj11, or Cmaj13 chord.

The most common way to make these chords is to play every note in the seventh chord and then add the extra note on top.

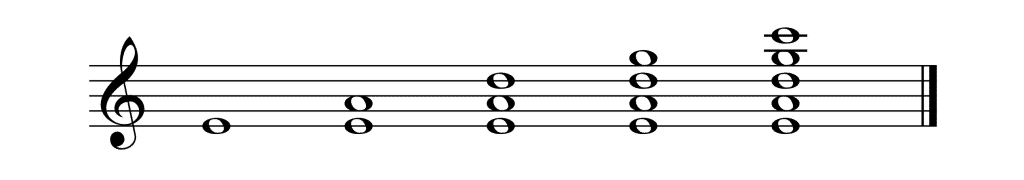

For example, in this style, a Cmaj9 chord would be C – E – G – B – D, a Cmaj11 chord would be C – E – G – B – F, and a Cmaj13 chord would be C – E – G – B – A as shown below:

If you’re playing a 13th chord, you don’t play the 9th and the 11th. You can add them in (so a Cmaj13 chord would be C – E – G – B – D – F – A), but that is a lot of notes, and it’s hard to make the chord not sound muddy.

Often, with extended chords, the first note to be dropped would be the 5th scale degree, so the G in C major. This keeps the flavor of the chord intact, and the 5th is sometimes seen as unnecessary.

A CMaj11 chord would then be C – E – B – F, or C – E – B – D – F.

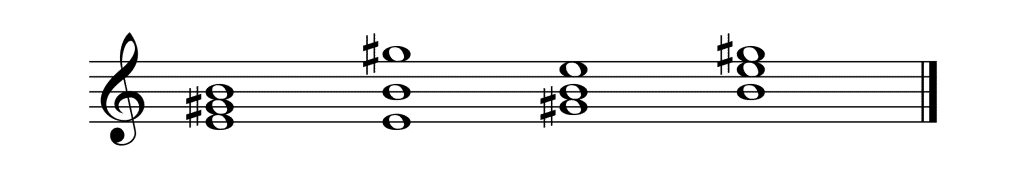

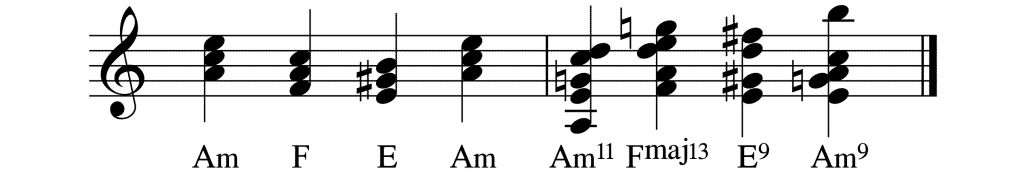

Here is the same chord progression played with regular triads (on the left) and extended chords (on the right):

Altered Chords

An altered chord is when one of the notes in a chord is changed either up or down by one semitone.

The tonic (1st), 3rd, and 7th can’t be changed because changing one of them more significantly affects the chord.

For example, if you have a C – E – G chord and change the 3rd down a semitone to C – Eb – G, that’s not an altered chord but a minor chord (which we’ll look at later).

The only notes that can be changed in an altered chord are the 5th and the extended scale degrees: not just the 9th, 11th, and 13th, but the 10th and 12th as well.

To alter a chord, you simply add the alteration to the end of the chord name.

For example, a CMin7#5 is a C minor 7th chord with the 5th raised a semitone: C – Eb – G# – Bb.

Also, a CMin7b9 is C – Eb – G – Bb – Db, a C minor 9th chord with the 9th lowered a semitone.

Non-Tertian Chords

All of the chords mentioned above with three or more notes in them (triad, tetrads, extended and altered chords) are based on the interval of the 3rd.

Each of those chords are essentially just 3rds stacked on top of each other. These are what we call tertian chords, meaning they are built out of 3rds.

However, there are also chords that are not built from stacking 3rds. Two of the most common ones are suspended chords and quartal chords.

Suspended Chords

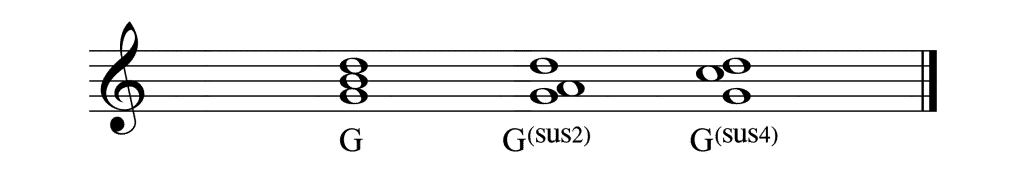

A suspended chord is a chord that has a suspended note within it. It is almost always a triad, and the 3rd of the chord is substituted for either a 2nd or a 4th.

For example, here is a G major triad (G – B – D), with the B substituted for the 2nd scale degree (G – A – D) or 4th scale degree (G – C – D).

Often suspended (also known as sus for short) chords are found in pop and rock music because it’s easy to make sus chords on a guitar.

A good example of a song that uses sus chords in its main chord progression is Free Fallin’ by Tom Petty.

This song starts with a common progression of D major (D – F# – A) to Dsus4 (D – G – A).

Another good example of sus chords in action is ‘Colorful’ by The Verve Pipe.

This song starts off with three sus chords in a row, and the first two are the two versions of an Asus chord.

It goes Asus2 (A – B – E) to Asus4 (A – D – E) and then to Dsus4 (D – G – A).

Quartal and Quintal Chords

If tertian chords are built on stacks of 3rds, quartal chords are built on stacks of 4ths.

These can be perfect 4ths (5 half steps) or augmented 4ths (6 half steps), but most songs with quartal harmony will have just perfect 4ths in their chords.

Let’s start with a C and then go up a perfect 4th to an F. From here, we have to go up a perfect 4th again, so we get a Bb (F – G – A – Bb), instead of a B♮ like we would if we were in C major.

A perfect 4th above a Bb is an Eb, and a 4th above that is an Ab, so a quartal chord built on C would be C – F – Bb – Eb – Ab.

One built on E would be E – A – D – G – C.

The piano part in Miles Davis’s song “So What” is a famous example of quartal harmony. Check it out:

There are also quintal chords, which are chords built by perfect 5ths.

For example, C – G – D – A would be a quintal chord, and so would B – F# – C# – G#.

The opening to Regina Spektor’s “Ode to Divorce” is an arpeggiated C – G – D – A quintal chord.

How to Notate Chords

When writing chord sequences in pop or jazz music, you don’t have to write out each chord note by note.

Composers and arrangers will often note the chord in shorthand, and there are a few symbols that are used to indicate different types of chords.

A major chord can be written as whatever note is the tonic of the chord + M, Ma, Maj, Δ, or (no symbol).

So a C major triad can be written as just “C,” or “CM,” or “CMa,” or “CMaj,” or “CΔ.”

When you have a 7th chord or an extended chord, you add the 7 (or whatever note) to the end, so you would have CMaj7 or CΔ11.

However, one tricky thing here is that C7, C9, or C13 do not mean a major chord.

A chord with just the note and then a 7, 9, 11, or 13 (e.g., D13, G11, or Eb7) means a dominant chord, and therefore the 7th in all of those chords is going to be a minor 7th.

So a C7 = dominant, it needs an extra symbol like CΔ7 or CMaj7 to mean it’s major.

Minor chords have the note followed by a lowercase m or min.

Examples would be Cm7, Am11, Ebmin, or Fm.

An augmented chord is a note followed by a + or aug (e.g., C+, Baug).

Diminished chords are noted by dim, and diminished 7th chords are noted by the o symbol for fully-diminished 7ths and the ø symbol for half-diminished.

For example, Cdim Bø7 or Ao9.

Summing Up

That’s it for chords!

There is a lot of information here and a lot of different chord qualities and numbers of notes, and they all come with their own rules and details you have to memorize.

We will be coming out with longer articles on some of the bigger sections and also adding a section about chord inversions, but for now, please email if you have anything to ask us!