In classical music, the Sonata is one of the most popular musical styles, as well-known as the terms Symphony or Concerto. It has its own form that has arisen from its name – this is called Sonata Form, though it’s also known as Sonata-Allegro Form or First Movement Form.

This post will cover everything there is to know about Sonata Form. First, however, we need to understand what musical form is.

What is Form in Music?

Analyzing musical Form is another way of looking at the structure of a piece of music, basically how it is put together.

Most (if not all) pieces of music can be broken down into sections.

These sections can be small or short, like a single bar or melody, or they can be long and intricate, such as a long passage or even an entire movement.

For example, a pop song could have the sections Verse 1, Chorus, Verse 2, Bridge, and it would move between them.

However, a single verse could be broken down into smaller sections, such as the first line of melody, second line, etc.

You then label each section with a letter – A, B, C, D, etc.

So, if a pop song goes Verse 1 – Chorus – Bridge – Chorus, it could be labelled ABCB.

Learn more about form, and all of the many different types, here in our guide.

Sonata Form – The Definition

Sonata Form is probably the most important musical form of the Classical era.

It is often called Sonata-Allegro Form or First Movement Form because it is typically used as the form of the first movement of a full Sonata, and the first movement usually has a tempo marking of “Allegro”.

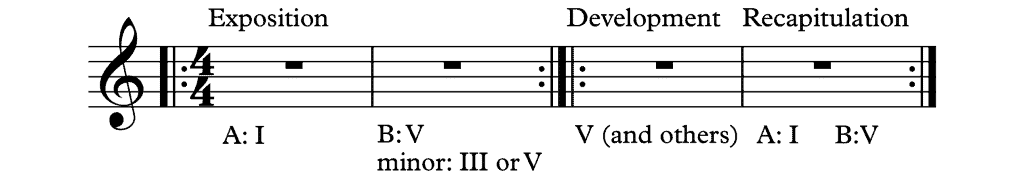

Sonata Form as a structure consists of three main sections:

- an exposition

- a development

- a recapitulation

Here is a diagram of roughly how the three sections work together, and how the Allegro first movement of a classical Sonata will be written:

Exposition

All pieces in Sonata Form have the Exposition right at the beginning.

Sometimes there is an Introduction, but this isn’t always the case and it isn’t officially considered part of the structure.

The exposition presents the main thematic material of the piece and establishes the tonic.

Just like there are different parts to a sonata, there are also different parts of the exposition – four to be precise. These are:

- the first subject group

- the transition

- the second subject group

- the codetta.

The First Subject Group, labelled “P” for “Prime”, consists of one or more themes, with all of them written in the main tonic key.

The Transition (“T”) is when the piece moves from the first key to the second key. If the first key is major, then the second one is the dominant (V). If the first key is minor, the second key would be the relative major (III).

The Second Subject Group (“S”) plays one or more of the “P” themes again, except this time in the second key. Often, the themes are essentially the same but more ornamental or with more flourishes or a different rhythm.

The Codetta (“K”) brings the exposition to a close with a perfect cadence in the key of the second group, “S”. The whole exposition section is usually then repeated.

Here is an example of sonata form; listen to the first movement of the “Sonata in G Major” by Haydn:

At around 0:08 the first subject group starts, with the melodic theme.

The transition to the V chord (D Major) occurs around 0:28 with the first accidentals.

The second subject group starts at 0:37, and then the Codetta is at 1:12, right before the whole thing repeats.

Development

The Development is the middle section of a piece in Sonata Form.

It starts in the same key that the exposition ended in (the V chord of the original tonic) and travels through a variety of similar or distant tonal centers.

It also restates the theme or themes of the exposition, however this time it develops them.

This means it alters the themes and presents them in different keys, or perhaps in a minor key, or it could have a different harmonic or rhythmic structure, and so on.

The development is the most unique part of each individual piece in Sonata Form.

Although the exposition and the recapitulation are roughly the same over different pieces of music, the development shows off each composer’s unique talents and different styles.

Take this development section from Mozart’s famous “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik”, first movement.

It is very short, it starts at 3:22 and then the recapitulation starts at 3:59.

In that short time, the tonal center travels from D Major through multiple different keys, such as B Maj, A min, D min, and C Maj, before settling back in G Major at the recapitulation.

The development of the first movement of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony, on the other hand, is very long and intricate.

It again starts at 3:22, but continues for over five minutes, changing to the recapitulation at 8:42.

Throughout the development, Beethoven uses many different syncopated rhythms and complex, dissonant key centers.

Recapitulation

The final section of a piece in Sonata Form is the Recapitulation.

Like its name implies, it is basically a restatement (or recap) of the main themes that were first presented in the exposition, except this time there is no transition to the V (or III in minor).

All of the themes are played in the original tonic key that started the piece.

The recapitulation starts, like the exposition, with a First Subject Group, which is again in the home key, as it was before.

Then there is a Transition, although this acts more as a “Secondary Development” section, and often adds new or unique material that was not in the exposition.

Lastly, there is a Second Subject Group, although this is again in the home key rather than the secondary key.

If the piece was overall in minor, this Second Subject Group might be replayed in the parallel Major to give the piece a happier ending.

Here is the recapitulation from Haydn’s “Sonata in G Major”, starting at 2:58. Back up the player a few seconds if you want to hear the end of the development and how it transitions back into the recapitulation.

Around 3:12 is when the Transition starts, although this time it doesn’t transition to anywhere but simply plays something unique and that echoes the development section from before.

The second subject group then starts around 3:22 again and gives the second theme from the exposition, but this time in G Major.

When the recapitulation ends is when the Sonata Form of the movement is said to end.

Sometimes there is extra musical material played after this part, but if that is the case it is always called a Coda, and is not considered part of the form.

Here is an example of a Coda, from Mozart’s “Piano Sonata No. 7 in C Major”.

The recapitulation finishes its material at 5:17, with the long D trill that then lands on the C.

The last 8 bars are then considered the Coda, and they end with another Perfect Authentic Cadence in the original home key.

Variations from the Standard Form

Above is the general form of a piece that, if it follows these rules, will be considered to have Sonata Form.

Not all pieces in Sonata Form follow these exact rules, however, as various composers and artists often like to put their own style on display by changing or breaking some of the rules.

For instance, sometimes the exposition has only one theme that is repeated from the First to Second subject groups.

This is called a monothematic exposition, and that one theme is used to establish a connection between the tonic and dominant keys, rather than playing one or more themes for each key.

Here is an example, Mozart’s “Sonata in Bb Major, K570”:

Another variation is when the exposition modulates to a key that is different from the V (or III in minor).

Beethoven is particularly known for doing this often.

For instance, the second subject group could be presented in the mediant (I Maj to III Maj) or submediant (I Maj to VI Maj) or even the parallel major or minor (I Maj to i min, or vice versa).

An example is Beethoven’s “Waldstein Sonata”, which modulates from C Maj at the start to E Maj (III Maj) for the second subject group:

Expositions could also have more than 2 main key areas, or even just one if the piece does not modulate at all (Chopin’s “Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Min” is a great example).

In another variation, the recapitulation sometimes was played in a key that was different from the original exposition tonic key.

This is often the subdominant (VI), such as in many pieces of Schubert.

Here is an example of his, “Sonata in E Major, D459” that recapituliates in the subdominant.

Summing Up

That’s the Sonata Form!

It is very common, and one of the most popular forms to teach in school.

You will most likely see it on exams or be asked to analyze it in class, so it is very important to know everything you can about it.