Music is a lot like a spoken language. It has grammar and structural rules that we can use to create phrases and longer passages like movements and symphonies. And just like language, there are specific parameters that can tell us how to play a specific note or chord

In this post, we’ll focus on what articulation means in music, the multiple different types of articulation you could potentially see, and how to play them.

Definition of Articulation

In music, articulation is a lot like punctuation in language. It tells us how to play a specific note or chord, outside of what specific note to play and for how long.

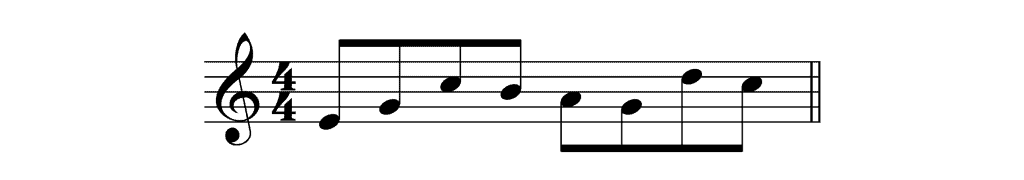

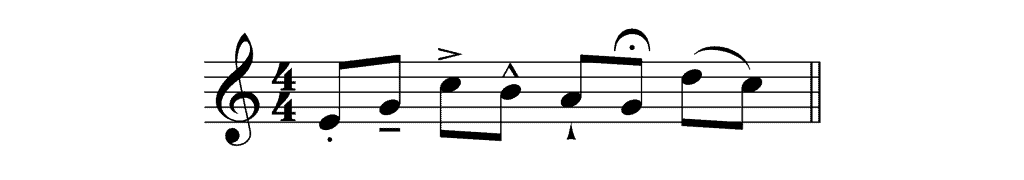

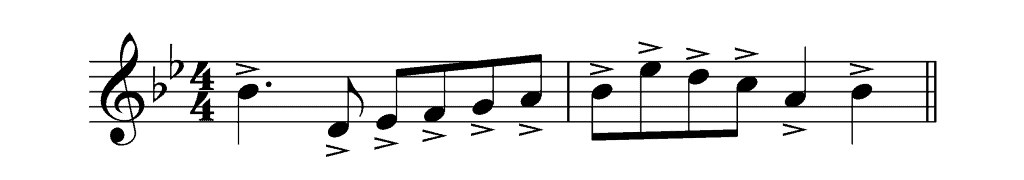

For example, let’s take a short melody:

The notes are in specific lines and spaces in the staff, and this tells us the pitches of the notes. The stems and tails of each note tell us they are all eighth notes (quavers).

The key signature on the left side (or lack thereof) tells us what key we’re in, and the time signature tells us how many beats per measure to play or sing. These things are always shown on all written music.

Articulation is an additional parameter that tells the musician how to play or sing the notes. Each of the notes in the melody above can be played really short and disjointed, or they can be long and flow into each other.

Some can be accented or quieted compared to others around it, and some can be connected and some kept separate.

Types of Articulation Marks

There are seven main articulation marks used in music.

These are:

- slur

- staccato

- staccatissimo

- accent

- tenuto

- fermata

- marcato

There are others, such as ornaments and dynamic markings like sforzando and (de)crescendo, but these are slightly different from articulation, and we’ll focus on just these ones for this article.

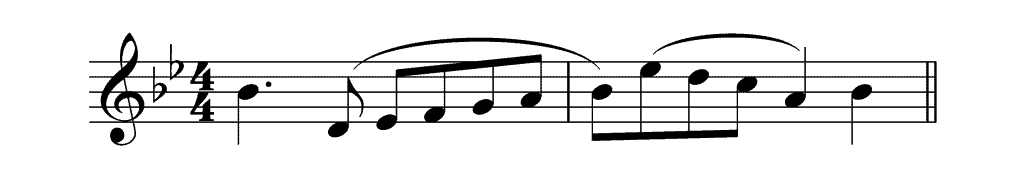

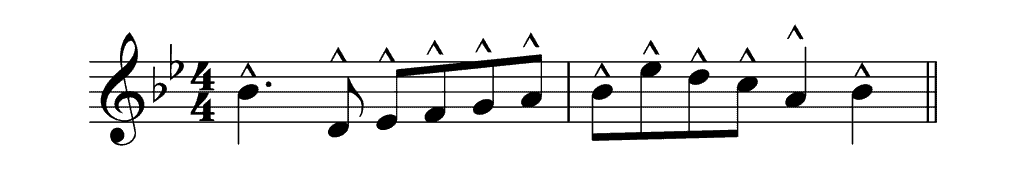

Here is the melody above, using all seven of the articulation marks listed:

Slurs (Legato)

A slur, also sometimes called a phrase mark, is the only type of articulation listed here that covers more than a single note. It indicates to the musician that they should play or sing multiple notes as one connected phrase.

For example, singers and wind instrument players shouldn’t take a breath between notes connected by a slur, and string instruments should play all of the notes with the same bow stroke.

This is called playing a phrase legato.

In the melody above, the slur is the curved line between the two notes at the end (D – C). You can also have slurs that last for more than two notes, such as the ones in the melody below:

Slurs are always between notes that are different pitches. Don’t get confused with tied notes, which are lines between notes that are the same pitch.

A good example of the use of slurs in music is the start of Mendelssohn’s “The Hebrides.” Each of the phrases are connected by slur markings and played legato:

For more information, check out our post here covering what is legato in music.

Staccato

The opposite of playing legato is to play a note staccato. From the Italian word for “detached,” staccato means to play a specific note or group of notes separate from each other.

Every note that has a staccato marking (a dot above or below the note head) is played very short and is not to be attached to the note after it.

The first note of the main melody above has a staccato mark below it.

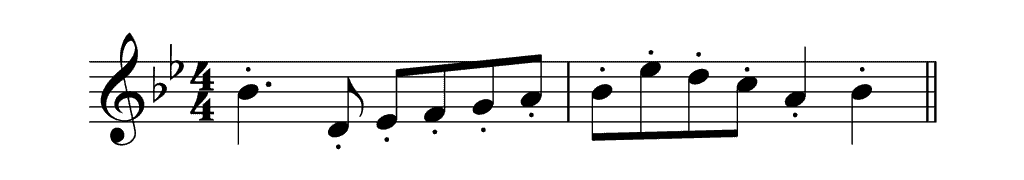

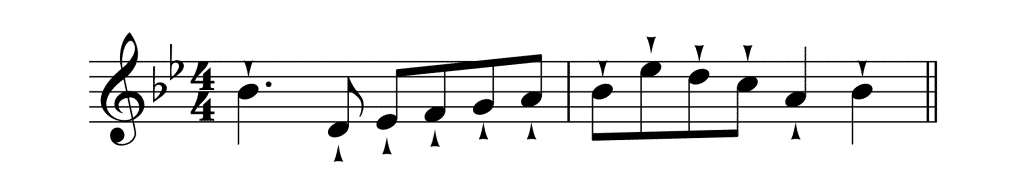

Here’s another example in which all notes are played staccato. Notice how when the stems of the note face down, the staccato dot is above the note head, and it’s below the note head when the stem faces up:

Here is an example from the beginning of Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto No. 3 in C min”. The descending lines in bars 2-3 and 6-7 are all played staccato:

Staccatissimo

In Italian, the suffix “-issimo” means “very” or “really,” so staccatissimo means to play the notes very staccato. This means extra short and keeps each note really detached from the ones around it.

In the main melody written above, the staccatissimo marking is below note #5 (the A) – it looks like a small, filled-in pyramid.

Here is a short melody with all staccatissimo markings. Again, like all of the articulation marks, it is written above notes with the stems pointing down and above notes with the stems pointing up:

An example of staccatissimo can be found in Beethoven’s “Sonata No. 21 in C Major”, at the 0:46 second mark, starting at bar 30:

Accent

An Accent mark looks like this: >. It is a mark that tells the musician to accent a specific note by playing or singing it louder and with a stronger attack than notes that don’t have an accent.

It doesn’t affect the length of the note, meaning you don’t have to make it shorter than written (like staccato) or longer than written (like legato).

The third note of the main melody has an accent mark over it. Here’s a short melody with all the notes accented:

Brahms uses accent in this passage in his “Piano Concerto No. 2 in Bb Major” to accentuate the triumphant melody:

Marcato

A Marcato articulation is like an accent mark but more intense. If staccatissimo means “very staccato,” think of Marcato as “very accented.”

It means to play the note or chord louder and more forcefully than the notes around it. It looks like a standing-up accent mark: ^. The fourth note (the B) of the main melody above has a marcato mark above it.

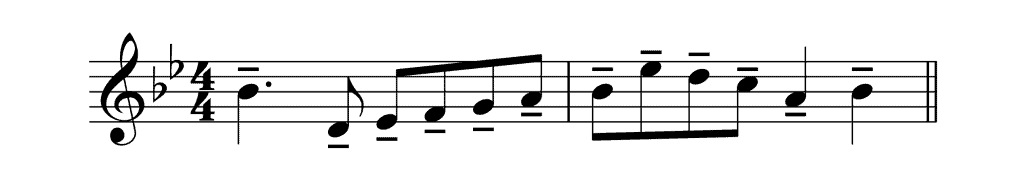

Here is another example. Notice that, unlike the accent mark, the marcato marking is always above the note it articulates, even if the note’s stem points upwards:

Tenuto

A Tenuto marking looks like a small line either above or below the note (again, depending on which way the stem is facing).

Meaning “to hold” in Italian, it is a direction for the musician to sustain the note that it’s marking for its full value.

This is different from legato playing, with slur markings, because you don’t necessarily merge one note into the following, and it’s different from staccato as well because you don’t want to shorten the note at all.

It can sometimes mean to play the note slightly louder and longer than the notes around it, making it stand out, or potentially holding the note a bit longer than it’s written.

The third note of the main melody above has a tenuto marking, as does each note in this melody here:

Scriabin uses tenuto markings in the opening piano solo in his “Piano Concerto in F# Minor,” starting at 0:23:

Fermata (Pause)

A fermata is the only articulation mark that really changes the beat of the music being played.

Also referred to as a pause or hold, it indicates to the musician that they should hold that specific note, chord, or rest for longer than its typical value.

Sometimes, this can be a small difference, and the note only played a bit longer than normal, but sometimes the conductor or player can hold the note for as long as they want, causing the music to feel like it’s suspended and build anticipation for the next note.

The fermata in the main melody above is on the third to last note, the G. It looks like an open circle facing down with a small dot inside it.

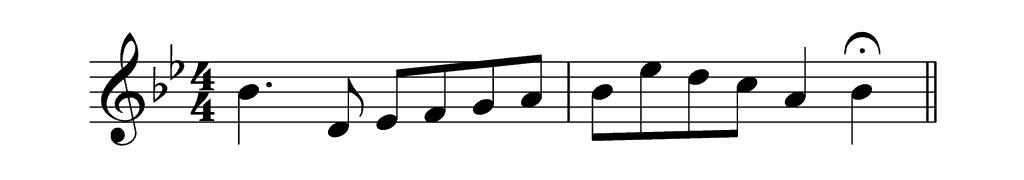

Here is another example of it (usually, it is found right before or at the end of a melody or a movement):

Here is an example from Beethoven’s “Piano Concerto No. 3 in C min”. Listen for the chord hold at 33:55 and then the single note hold (on G) at 34:14:

Instrument Specific Articulation

Articulation can vary depending on which instrument you are playing or if you’re singing in a choir.

For example, woodwind and brass players create articulation by tonguing, which is the use of the tongue to create and restrict airflow.

For these instruments, you can play legato by using the flat of your tongue, like in the word “la,” or play staccato by using the tip of the tongue, as in “tah”.

With a stringed instrument, you can play pizzicato, which is plucking the string with your finger. This causes the notes to sound staccato but is different from regular staccato markings.

Playing with a bow rather than your finger is called arco, and you can play staccato, tenuto, or legato, all using a bow as well.

Legato is when you let the string vibrate between notes so that the sound of the note is sustained until the next note is played.

To play more staccato, touch the string with your hand or the bow to stop it from vibrating in between notes.

That’s it for Articulation

There are a lot of different articulation markings and even many more rare ones that this article doesn’t cover.

They can also be used to different effects in different contexts, so always check with the conductor or other players when you come across an articulation mark to make sure you know what they expect from it.